March 2018 - Diversity, Inclusion and Leadership Study

Discover the "diversity, inclusion and leadership" survey carried out by the Chair in 2018, which analyses the representations of leadership and the way in which diversity and inclusion in companies can drive performance.

HOW TO ADVANCE DIVERSITY AND THE CLIMATE OF INCLUSION IN COMPANIES?

Equality issues, and more generally diversity and inclusion, have been a major concern for organisations, and in particular for large companies, for some years. However, whether they are motivated by simple compliance with non-discrimination laws, the personal conviction of managers or the search for performance and increased reputation (APEC, 2015), the efforts made in favour of equality and diversity have clearly not yet fulfilled all their promises. This is the finding of several surveys that point the finger at discrimination in hiring and career development (TNS Opinion & Social for the European Commission's Directorate-General for Justice and Consumers, 2015), wage inequalities between women and men (Eurostat, 2017) or the persistence of gender stereotypes (Mediaprism and Laboratoire de l'égalité, 2012). This is also the finding of the Chair in this study, which measures the perceptions of 767 employees on diversity and inclusion within their companies.

Beyond the findings, this study tests a set of hypotheses on how diversity and the climate of inclusion can progress in companies. Specifically, the objectives of this study are:

- To assess how employees judge their organisations in terms of diversity, gender equality and climate of inclusion.

- To reveal their perceptions of leaders and leadership.

- To measure the leadership style and effectiveness of respondents' managers.

- To identify the links between diversity, inclusion, leadership and human performance.

SEE THE VIDEO PRESENTATION OF THE RESULTS

DIVERSITY, INCLUSION AND GENDER EQUALITY, WHAT ARE WE TALKING ABOUT?

The concepts of diversity, inclusion and gender equality are difficult to quantify. It is indeed possible, for example, to compare the proportions of women and men at each hierarchical level of a company without being able to really assess the level of equality within the same company. In fact, the mere fact that the proportions of women and men at the various hierarchical levels are comparable does not indicate whether access to responsibilities is based on equivalent effort and skills.

This study set out to measure employees' perceptions of diversity, inclusion and gender equality in their companies using scientifically validated measurement tools. In particular, the researchers relied on measurement scales. These are sets of questions that make it possible to assess the perception of respondents of a complex concept (in this case, the extent to which they feel their company is involved in issues of diversity, inclusiveness and equality in the promotion of women and men). The construction and analysis of the measurement scales follow a rigorous methodology that is now well known and mastered in the social sciences (Hinkin, 1998).

REASSURING RESULTS, BUT THERE IS STILL SOME WAY TO GO

The employees who responded to the survey perceive their company as relatively diverse and inclusive. The average score given is 6.2/10 and 5.5/10 respectively. With regard to gender equality, respondents are more critical and give an average score of 4.9/10.

This shows that although the results are not alarming, companies can do significantly better to make their employees feel fully included and equal in the workplace.

Employees were asked questions such as 'My company has a culture where differences are seen as a strength', which are part of scientifically validated measurement scales for perceptions of diversity, climate of inclusion and gender equality. Scores are given between 0 and 10 (0 expresses a perception of no level; 10 expresses a perception of a perfect level).

DIVERSITY, INCLUSION AND EQUALITY: DIFFERENT PERCEPTIONS BETWEEN WOMEN AND MEN...

The question then arose as to whether women and men had the same perception of diversity, inclusion and gender equality in their companies. The answer is no. The overall results in fact hide different perceptions depending on the gender of the respondent but also on whether they are managed by a woman or a man.

Women are more critical in their perceptions than men, especially on the subject of equality. On average, women respondents rate their companies as less equal than male respondents, with average scores of 4.1/10 and 6.8/10 respectively. Are women more aware of the issue and therefore rate their companies more harshly? Or do men not perceive all the inequalities still present, being less concerned themselves? The question remains open.

In terms of gender equality, differences also appear according to the gender of the respondents' manager. Respondents whose manager is a woman perceive their company as more equal (score of 5.3/10 compared to 4.6/10 if the manager is a man). They feel that there is less of a gap between women and men in terms of the effort required to reach positions of responsibility. Female managers therefore seem to contribute to the feeling of equality within the company.

WHAT IF WE USED THE LEVER OF LEADERSHIP TO ADVANCE DIVERSITY AND INCLUSION IN ORGANISATIONS?

The three levers usually used in companies to advance equality and diversity (Kalev, Kelly and Dobbin, 2006) are:

- The creation of a dedicated diversity management department that sets targets, action plans and evaluation systems for other departments and reports back to the company's management;

- the implementation of training and awareness-raising programmes to raise awareness of inequalities, stereotypes and actions to be taken in favour of diversity;

- Developing mentoring and networking programmes to support the integration and promotion of women and minorities through the promotion of interpersonal relationships.

As noted in several studies (Kalev et al., 2006; Dobbin and Kalev, 2016), these efforts, some of which have been going on for more than three decades, have mostly produced progress in companies, but it is slow and often insufficient.

The question is therefore: how to accelerate the progress of diversity and inclusion?

The proposal of the Chair's researchers is to impulse a transformation of behaviours and representations of leadership in order to:

- Allow diversity to be expressed in all areas and at all levels of the organisation.

- Create an inclusive organisational climate.

Indeed, the authors argue that diversity and inclusion is not just a question of gender, age, origin or any other attribute, it is above all a question of representations and practices of power. Their conviction is that changing the perspective by putting leadership and its representation at the heart of diversity policies will lead to effective and sustainable transformations for diversity and inclusion in organisations.

In order to verify this hypothesis, the researchers included in the study questions:

- on the representations of leadership, which allowed them to draw up an inventory of the existing situation;

- on the leadership of the respondents' managers to assess the links between leadership, diversity, inclusion and human performance.

POINTS TO REMEMBER

Over the last three decades, companies have been implementing strategies firstly for gender equality, then for diversity and more recently for inclusion. The findings of the academic and professional literature show that progress has been made but that much remains to be done, as confirmed by the results of this study. In particular, the results highlight that women judge their companies more harshly in terms of equality. Companies are looking for new levers to accelerate the move towards greater inclusion and equality. The assumption made by this study is that transforming leadership models would open up leadership positions to a greater diversity of talent, thereby contributing to business progress.

WHAT IS LEADERSHIP?

For more than a century, researchers (in various fields such as psychology, political science and management science) have been exploring and analysing the concept of leadership. According to Northouse (2010): 'Leadership is the process by which an individual influences a group of individuals to achieve a common goal'.

Leadership is therefore the ability of an individual to convince, motivate and unite a group of people without having to rely on his or her possible status or hierarchical position and without using means such as coercion, manipulation or dishonesty.

To this must be added the purpose of leadership, which is to engage a group of people in order to achieve a collective goal and succeed in a transformation project. Indeed, according to Rost (1993:92): 'Leadership is a relationship of influence between a leader and followers whose common goal is to achieve real change'.

REPRESENTATIONS OF LEADERSHIP

The researchers wished to examine what representation of leadership the respondents have. To this end, they were asked to spontaneously associate 3 words with the term 'leadership'. The results show a clear dominance of vision and charisma over the other terms mentioned. The respondents therefore still have a romantic or heroic vision of the leader: a person who has a vision and is capable of taking everyone with him or her through charisma alone.

These results are consistent with the results of other studies conducted by the Diversity & Inclusion Chair at EDHEC (see Petit & Delanghe, 2015 ; or Petit, Jemel, Delanghe & Houriet Segard, 2017.

The authors also asked respondents about the characteristics of good leaders. They were given a list of 20 traits and asked to rate how important they thought these were for good leadership (on a scale of 0-10).

These 20 traits are categorised into two groups of ten: traits socially defined as 'feminine' and traits socially defined as 'masculine' (The traits are taken from a measurement scale validated in the academic literature, Bem, 1974). For example: Being authoritative is a trait socially associated with 'masculinity' while being sincere is a trait socially associated with 'femininity'.

It is important to emphasise that this is not to say that all women must be sincere and all men must be authoritative or conversely that men cannot be sincere and women cannot be authoritative. In reality, all the attributes tested can be adopted equally by men and women. However, it is the weight of social representations, still rooted in thought patterns, that leads individuals to associate certain characteristics with a particular gender. These are typically stereotypes that distort the way in which the expected roles of women and men are represented in our societies and that persist to this day even in developed Western countries.

In this study, the traits most associated with good leaders are predominantly 'male'. To be perceived as a good leader, one must be strong and energetic, willing to take risks and have authority. However, one must also be sensitive to the needs of those around him and be sincere.

HOW WAS LEADERSHIP ASSESSED?

The authors asked the employees consulted to evaluate the leadership of their direct manager.

The latter is evaluated on two aspects:

- Leadership effectiveness.

- Leadership style.

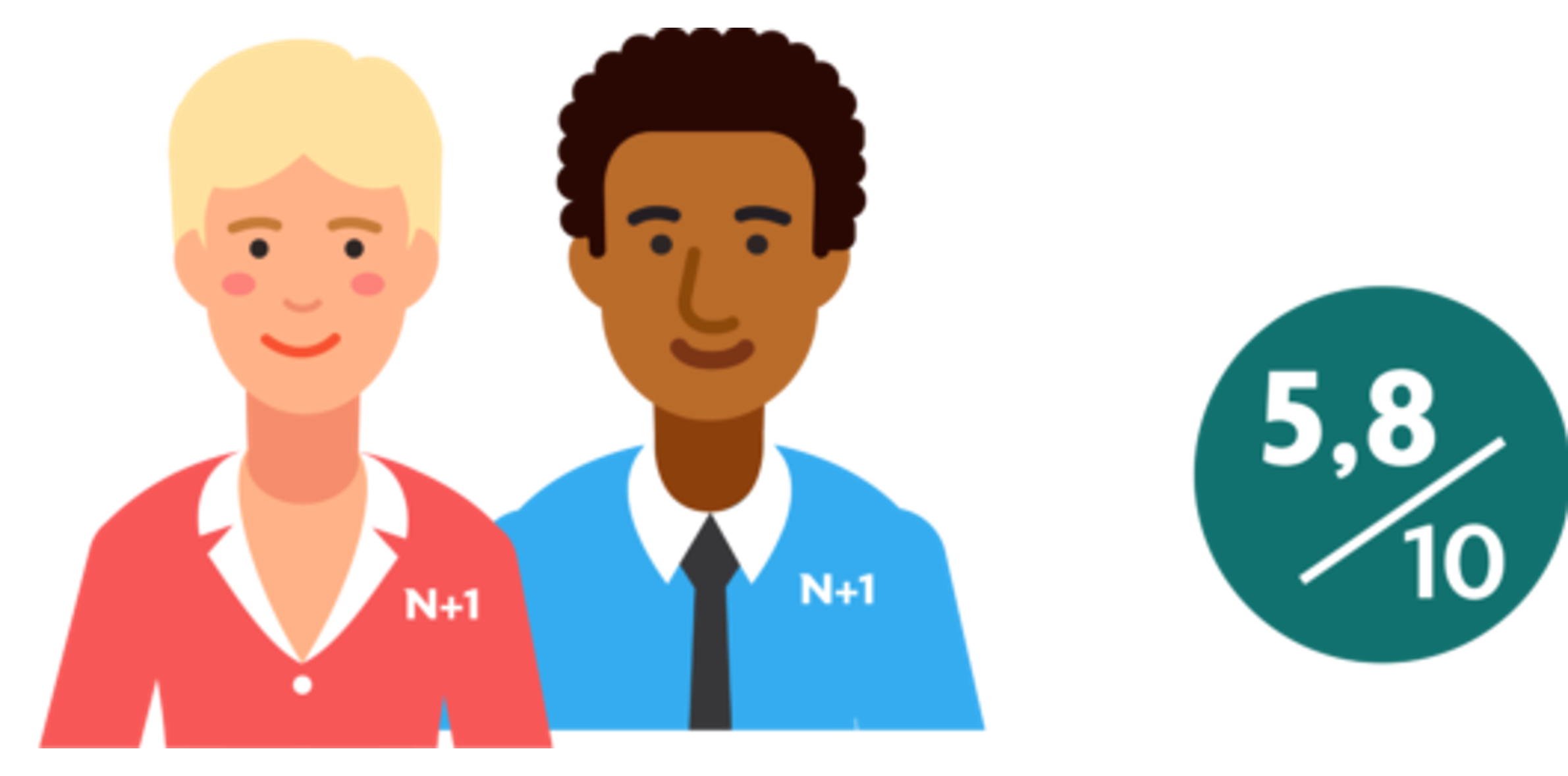

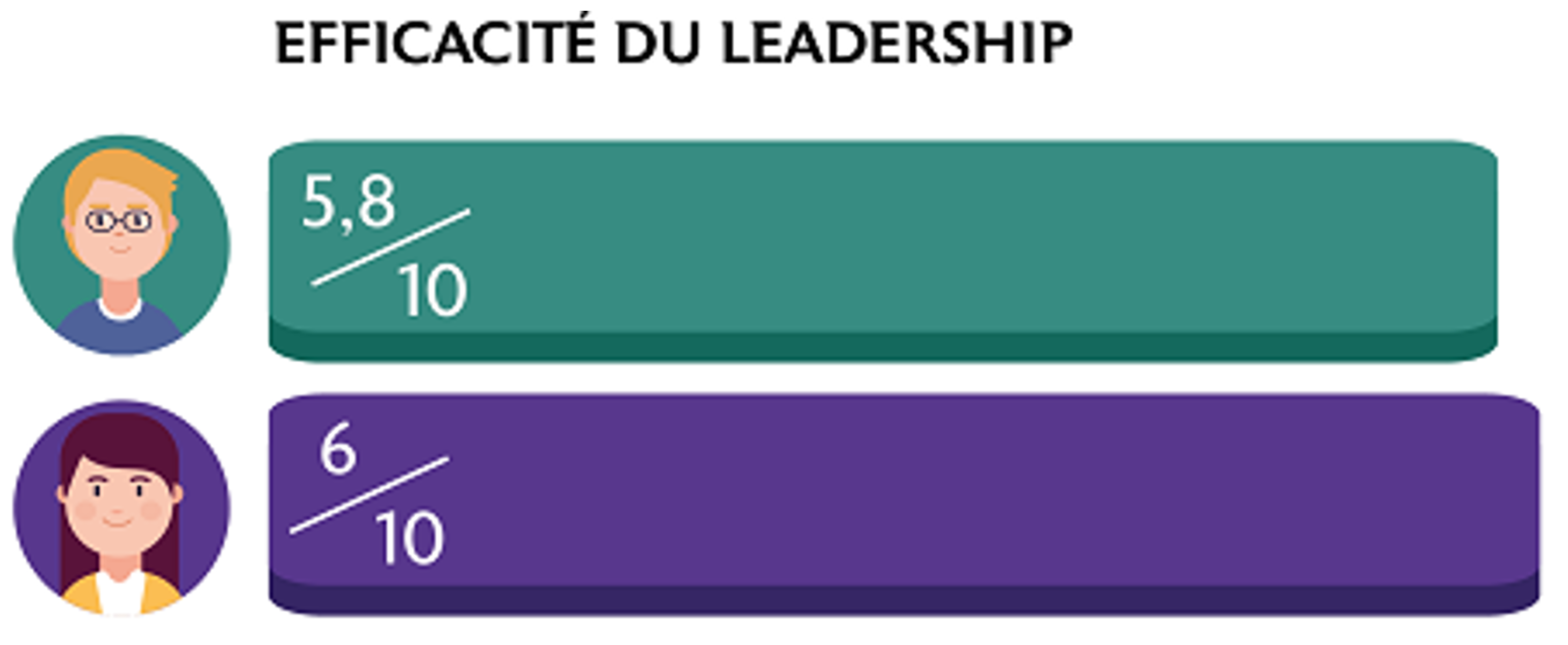

Leadership effectiveness is measured indirectly by means of a scale consisting of several questions assessed with scores from 0 to 10. The leadership effectiveness of the manager assesses the extent to which the manager is able to lead a group towards a common goal while defending the interests of the group, meeting its needs and collaborating satisfactorily. The results show that respondents rate the leadership effectiveness of their manager at 5.8/10. This score is in line with the results obtained in previous studies by the Chair (5.9/10 on a sample of private sector managers), see Petit & Delanghe, 2015 and 5.5/10 on a sample of public sector managers, see Petit, Jemel, Delanghe & Houriet Segard, 2017. Overall, it indicates a leadership deficit of the managers concerned.

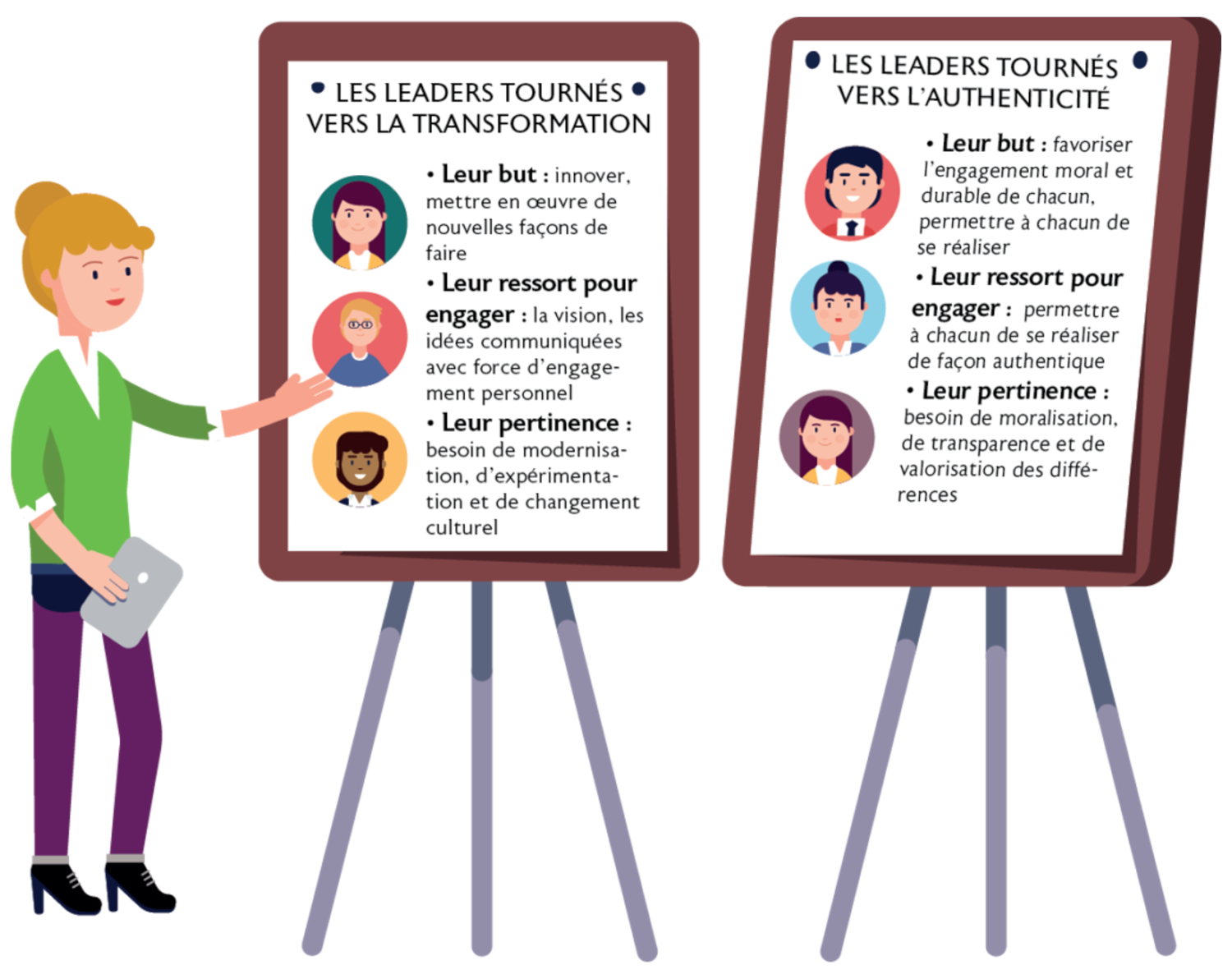

There are several leadership styles. A style is a set of behaviours adopted by a leader to obtain the support of a group of people, their motivation and their involvement in achieving a common goal. In this study, the researchers analysed two leadership styles that are known to be effective in the literature. It should be noted that leadership is a highly contingent phenomenon according to leadership researchers: that is, it cannot be reduced to the qualities of the leader alone. More precisely, we can say that a person expresses leadership if and only if his or her behaviours correspond :

- the expectations of the stakeholders or followers ;

- the requirements of the situation.

Not all leadership behaviours are therefore effective in all situations and with all teams.

However, the two styles assessed here (transformation-oriented leadership and authenticity-oriented leadership) are recognised in the academic literature to be among the most effective in general.

It is also important to note that the same person may have dominant traits associated with one leadership style and use, depending on the circumstances and stakeholders, other leadership behaviours from a variety of styles.

As the illustration below shows, authenticity-oriented leadership and transformation-oriented leadership have different goals and behaviours and are more relevant in some contexts.

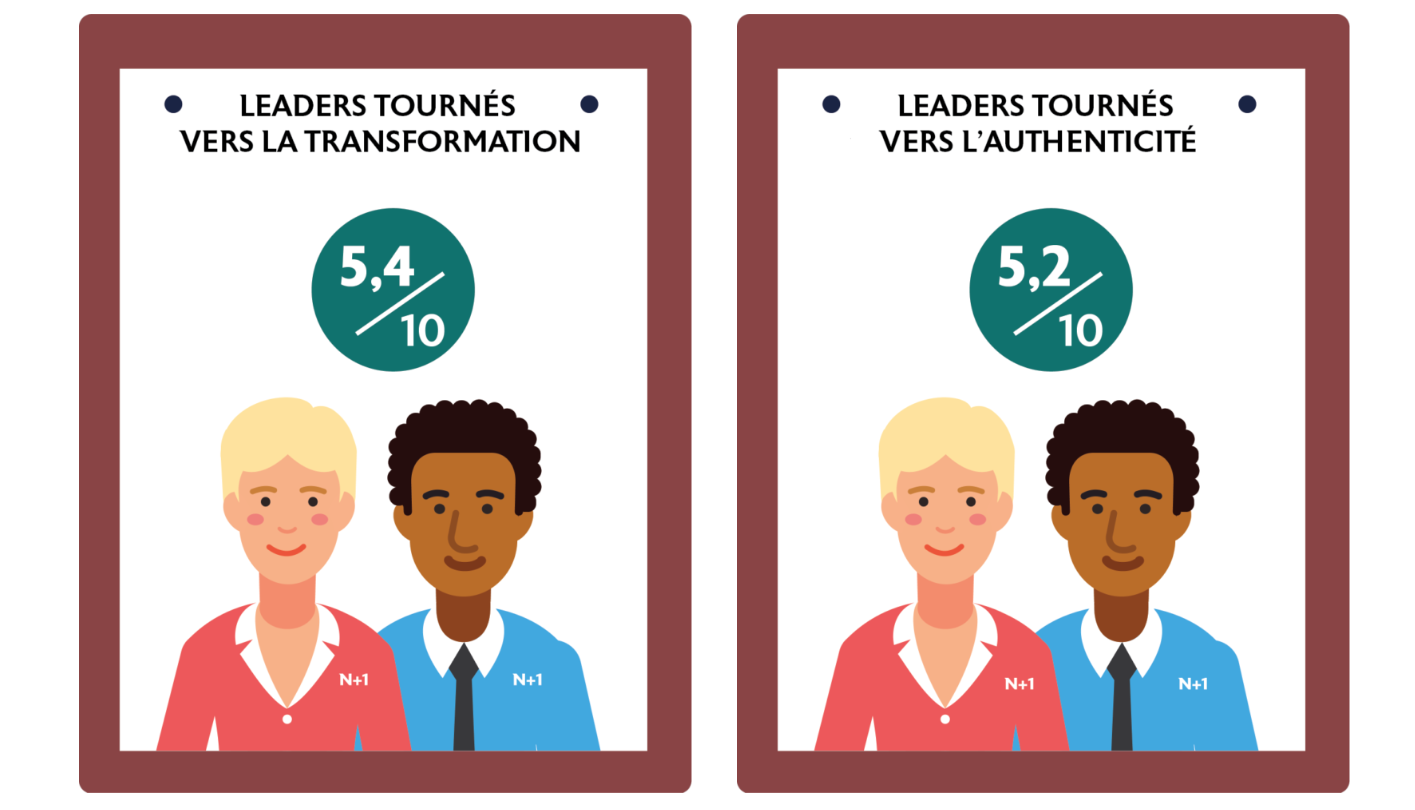

The scores obtained by the respondents' managers are fairly balanced between the two styles (5.4/10 for authenticity-oriented leadership and 5.2/10 for transformation-oriented leadership). There is significant room for improvement in both styles. Nevertheless, as for leadership effectiveness, the scores obtained by these managers are not very different from those attributed to French managers in the Chair's previous studies. Indeed, in terms of authenticity-oriented leadership, French private sector managers scored 5.7/10 while public sector managers scored 5.4/10. In terms of transformational leadership, the scores were 5.5/10 and 5.6/10 respectively..

WOMEN, MEN AND LEADERSHIP: NO SIGNIFICANT DIFFERENCE

Questions often asked about the leadership of women and men are:

- Do women and men lead equally well?

- Do women and men exercise leadership in the same way?

According to academic research (see Petit & Saint Michel, 2016), there is no significant difference between women and men in leadership. This statement is verified on the managers of the respondents in the sample.

With regard to their leadership effectiveness, male managers are given an average score of 5.8/10 while female managers receive a score of 6/10.

In terms of leadership styles:

- Authenticity-oriented leadership is rated at 5.3/10 for male managers and 5.5/10 for female managers.

- Transformative leadership is rated 5/10 for male managers and 5.5/10 for female managers.

So it seems that women have a very small advantage over men when it comes to leadership. However, statistical analyses show that the scores between female and male managers are not significantly different.

POINTS TO REMEMBER

The representations of leadership and good leaders of the respondents in this study are still very traditional and socially connoted as masculine, imbued with the notions of charisma, decision making and risk taking. This result is in line with those of other studies conducted by the Chair on different populations. The results of this study also point to a leadership deficit among managers, with scores that are slightly above average. Finally, contrary to general belief, there is no difference in leadership (either in the level of effectiveness or in the way leadership is exercised) between women and men (see Petit & Saint Michel, 2016, to learn more about this topic).

THE BUSINESS CASE FOR DIVERSITY AND INCLUSION: WHEN DIVERSITY AND INCLUSION IMPROVE PERFORMANCE

Making the business case for diversity (Garner-Moyer, 2006) consists of demonstrating the positive impact of progress in diversity and inclusion in the company on its performance (whether economic or human performance such as the reinforcement of the company's values, the attractiveness of the company for talented employees, employee motivation or satisfaction etc).

In this study, the researchers assessed the relationship between diversity and inclusion on the one hand and human performance on the other. In terms of human performance, they measured respondents' motivation and job satisfaction as well as their satisfaction with their manager. They also studied the links between diversity and inclusion and the effectiveness of the direct manager's leadership.

These relationships are assessed using correlation analyses and more advanced statistical tools (linear regressions and structural equation models). The results presented are statistically significant (see methodology).

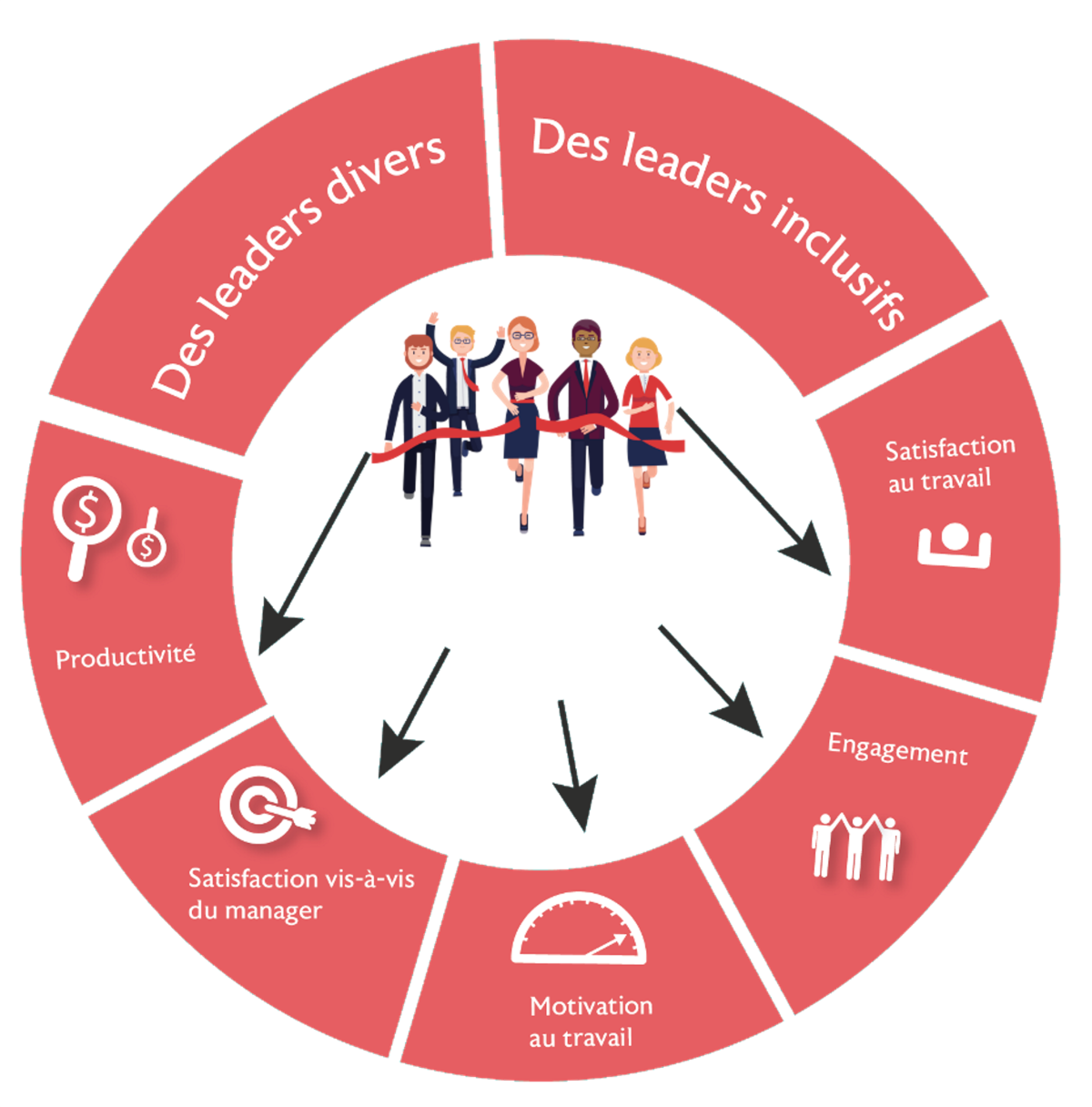

As the illustration above shows, these analyses support the business case for diversity. Indeed, there is a very strong positive relationship between employees' perception of the diversity and inclusion climate in their company and their level of satisfaction, motivation and satisfaction with their manager. A better diversity or inclusion climate is also linked to more effective leadership by managers. These positive relationships also exist when we look at the respondents' perception of gender equality in their company, albeit in a less intense way. This suggests that the mere consideration of gender in companies has a positive effect on human performance, but this is much more important when other dimensions of diversity are also considered.

A VIRTUOUS NETWORK: WHEN LEADERSHIP BECOMES A BUSINESS CASE FOR DIVERSITY AND INCLUSION

There is still a lot of progress to be made in terms of diversity and inclusion (and gender equality) in companies. This progress is necessary and important from an ethical point of view, of course, but also for better business performance (economic and human). In order to accelerate progress, the researchers of the Diversity & Inclusion Chair propose to reinforce the effectiveness of classic diversity management systems by transforming the representations and models of leadership in the organisation.

The representation of what a leader is and the attributes of good leaders is still very much centred on a romantic and reductive vision placing charisma and vision in a central position to define leadership. The leader is still, in the collective imagination, the hero who takes decisions with authority, who is not afraid to take risks, the one who will save the situation and convince everyone thanks to his charisma alone. This representation and the traits associated with good leaders are also traits socially associated with 'masculinity' in social representations. These cognitive patterns therefore exclude from the population of potential leaders a large part of the talent present in companies (women, of course, but also a whole diversity of talent and even men who do not correspond to these social representations). The hypothesis is that the transformation of leadership models would make it possible to open up positions of responsibility to a greater diversity of talent, thereby contributing to companies' progress in terms of diversity and inclusion. The promotion of diverse talent in all hierarchical positions would foster an inclusive climate and improve company performance.

The authors therefore believe that leadership must be part of the diversity business case equation and that the interactions between diversity and inclusion, leadership and human performance form a virtuous network that ultimately leads to more diversity and inclusion in companies, more effective and inclusive leaders and improved performance.

They conducted an initial test of these hypotheses using statistical analyses of the interactions between the observed variables. The results show that the relationships between diversity and inclusion and effective leadership styles (transformation-oriented and authenticity-oriented leadership) are strongly positive and significant (in the statistical sense). Diversity, inclusion and leadership also have a positive impact on measured human performance (job motivation, job satisfaction and satisfaction with the manager). Similarly, managers' leadership is also more effective in the presence of high diversity and inclusion scores and vice versa.

CONCLUSION

Diversity and inclusion in companies are vectors of economic and human performance (employee well-being, motivation at work, attractiveness of the company, etc.). The results of this study show that when leadership is added to the equation, these relationships are strengthened and a positive dynamic is created between diversity, inclusion, leadership and human performance. In order to accelerate progress in diversity and inclusion, the Chair proposes that companies, while continuing and improving their diversity management efforts, adopt a new approach by transforming leadership representations and behaviours.

In conclusion, the challenge is to change the representation of the leader in order to :

- Open it up to the diversity of talents.

- Encourage more inclusive leadership.

- Improve performance and well-being in the company!

SURVEY METHODOLOGY

This study was conducted in partnership with the Professional Womens' Network (PWN) Paris, which has been working for over 20 years to support the professional development of women. The results are the result of a quantitative survey of a sample of employees interviewed online during 2015. The survey was deployed in several waves to different French and international audiences, described below.

The assessment of gender equality, diversity and inclusion is based on scientifically validated scales that measure employees' perceptions of these issues within their company (11-point Likert scale allowing a score from 0 "Strongly disagree with the proposal" to 10 "Strongly agree with the proposal"). The leadership assessment is based on scientifically validated scales that quantify, via the employees' responses, the average frequency of leadership behaviours (effective leadership behaviours or behaviours typical of a leadership style) in their direct manager (11-point scale from 0, lowest score, to 10, highest score).

With the exceptions specified in the study, all results presented are statistically significant, i.e. it is 95% certain that the differences in results highlighted between sub-populations are reliable and not due to sampling chance.

As any survey does not interview the entire target population, it may be subject to respondent selection bias. The results should therefore be generalised with caution.

REFERENCES

- Apec (2015). Représentations et pratiques de la diversité dans les entreprises. Les études de l’emploi cadre, 2015-82, Consulté le 21 décembre 2017.

- Avolio, B.J., Gardner, W.L., and Walumba, F.O. (2007). Authentic leadership questionnaire. Published by Mind Garden, Inc., www.mindgarden.com.

- Bem, S.L. (1974). The Measurement of Psychological Androgyny. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 4(2), 155-162.

- Carless, S.A., Wearing, A.J., Mann, L. (2000). A short measure of transformational leadership. Journal of business and psychology, 14(3), 389 – 405.

- Dobbin, F., & Kalev, A. (2016). Why diversity programs fail. Harvard Business Review, 94(7/8), 52 – 60.

- Eurostat, 2017. The life of women and men in Europe, A statistical portrait. Consulté le 21 Décembre 2017.

- Garner-Moyer, H. (2006). Gestion de la diversité et enjeux de GRH. Management & Avenir, 7(1), 23-42. doi:10.3917/mav.007.0023.

- Hinkin, T. R. (1998). A brief tutorial on the development of measures for use in survey questionnaires. Organizational Research Methods, 1, 104-121.

- Kalev, A., Dobbin, F., & Kelly, E. (2006). Best practices or best guesses? Assessing the efficacy of corporate affirmative action and diversity policies. American Sociological Review, 71(4), 589 – 617.

- Mediaprism, & Laboratoire de l’Egalité (2012). Egalité hommes-femmes et lutte contre les stéréotypes: Perception et attitudes des Français-es, Rapport d’enquête. Consulté le 21 Décembre 2017.

- Petit, V., & Delanghe, M. (2015). La révolution du leadership.

- Petit, V., Jemel, H, Delanghe, M., & Houriet Segard, G. (2017). Promesses et paradoxes du leadership public.

- Petit, V. (2013). Leadership, l’art et la science de la direction d’entreprise. Pearson.

- Petit, V., & Saint-Michel, S. (2016). Hommes, femmes, leadership, mode d’emploi. Pearson.

- Rost, J.C. (1993).Leadership for the twenty-first century. Greenwood Publishing Group.

- TNS Opinion & Social (2015). Special Eurobarometer 437, Discrimination in the EU in 2015. Request of the Directorate-General for Justice and Consumers, Co-ordinated by the Directorate-General for Communication, Consulté le 21 Décembre 2017.

- Yukl, G.A. (2010). Leadership in organizations, Seventh Edition. Prentice Hall.

THE AUTHORS

HAGER JEMEL

Chair Director, Professor of Management

MARIEKE DELANGHE

Researcher

GENEVIÈVE HOURIET SEGARD

Researcher

VALÉRIE PETIT

Professor of Management Founder of the Chair

PARTENAIRE DE L’ETUDE

This study was carried out with the support of the PWN Paris network.

The PWN Paris network has been working for over 20 years to support women's professional development.